The 1999 Popular Consultation

The process that led to the 1999 Popular Consultation, which gave autonomy to East Timor, was long and cumbersome. Self-determination was first considered in 1974 when Portugal decided to give autonomy to its colonies. However, Indonesia took over the territory in 1975 and sponsored an assembly which voted for its incorporation into Indonesia as one of its provinces. Resistance to this status was met with coercion. In 1998, the new president of Indonesia, B.J. Habibie decided to consider giving a special autonomy status to East Timor. The negotiations between Indonesia, Portugal, and East Timorese actors on the details of the autonomy opened the door for considering a self-determination option. The referendum to decide between those two alternatives took place on August 30, 1999. This history can be read below.

Independence from Portugal

After the military dictatorship was ousted in Portugal in 1974, the new government desired to change the status of its colonies, one of which was East Timor, considered until then as “overseas provinces”. In 1975 a law was passed giving these territories the right to self-determination and independence. The newly appointed Portuguese Governor for East Timor, Mário Lemos Pires, legalized parties in preparation for the elections of a Popular Assembly. It was expected that this body would meet in 1976, from which a transitional government would emerge, preparing the stage for Portuguese retirement in 1978.

Within East Timor there was no agreement on the path to follow. Three main parties emerged after the 1975 law. The Timorese Democratic Union (UDT) originally supported to continue under Portuguese rule, but later went for independence. The Revolutionary Front for and Independent East Timor (FRETILIN) also was for autonomy. The Timorese Popular Democratic Association (APODETI) was for an integration with Indonesia as an autonomous province.

In the elections for the Popular Assembly UDT and FRETILIN came as the most voted parties. This sprouted two fears in the Indonesian government. First, having eliminated the Communists during the 1960’s, it feared that what it saw as a Marxist-oriented FRETILIN would acquire strength. Second, it was preoccupied that a sovereign East Timor would serve as an example to other provinces seeking independence. In response, Indonesian military leaders held talks with UDT to let them know that, regardless of its status in relation to Indonesia, they would not tolerate East Timor being administered by FRETILIN. Ultimately, the pro-independence UDT-FRETILIN alliance broke up.

In August 1975, UDT launched a coup against FRETILIN, but failed. In the midst of an increasing confrontation between these two and other political, the Portuguese governor fled. At the same time, UDT members went to Indonesia, but were asked to fight for the integration of East Timor into Indonesia.

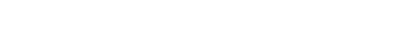

On November 28, FRETILIN unilaterally declared the independence of East Timor and the establishment of a sovereign republic. Neither Portugal, Indonesia, nor the neighboring Australia recognized this move. In response, Indonesia had UDT, APODETI and other organizations sign a declaration of integration of East Timor to Indonesia.

Indonesian Control

On December 7, Indonesia launched an air, land, and sea campaign against FRETILIN. Weeks later, a pro-Indonesian UDT-APODETI government was installed. In May 1976, a similarly Indonesia-sponsored Regional Popular Assembly of East Timor held its only meeting. It asked Indonesia to integrate the territory as a new province. On July 17, Indonesian President Sukarno promulgated the law integrating East Timor as the country’s twenty-seventh province. This move was not recognized by Portugal, which never formally ceased to be responsible for the administration of East Timor, neither by the United Nations, which had not been in any way involved in the procedures that led to the incorporation of East Timor into Indonesia. Yet, Indonesia took control over East Timor.

The Indonesian administration tried to pacify the province with its army and with the support of paramilitary groups. Yet, it was unable to counter guerrilla activities. This continued conflict provoked the displacement of people and famines due to insufficient agricultural production. As a result, an estimate of 200,000 people, a fourth of the population of East Timor, died or was forced to leave their homes.

Except for Portugal and the U.N., the international community gave its tacit support, or expressed no public condemnation, of Indonesia’s actions. The conflict through the 1970’s and 1980’s did not receive much attention from abroad. This changed in 1991, when pro-Indonesia militias opened fire against a demonstration of mourners in a cemetery near the East Timor capital, Dili, killing around 200 people. Images of the massacre were broadcasted in the international media, increasing awareness of the conflagration.

Portugal tried to apply some pressure on Indonesia. It gave pro-independence leader Xaxana Gusmao its highest honor after his detention in 1993. It also encouraged other members of the European Union to cut their diplomatic and commercial ties with Indonesia. Similarly, the Australian public opinion pressured its government to relinquish its close association with Indonesia given the abuses in East Timor. A peak in international attention came when in 1996, Bishop Carlos Belo and José Ramos Horta received the Nobel Peace Prize “for their work towards a just and peaceful solution to the conflict in East Timor”, as acknowledged by the award committee. Belo was recognized as a spokesman for non-violence and dialogue with the Indonesian Government, among whose ideas was the decision by popular referendum of the status of East Timor, and Ramos Horta for being the leading international spokesman for East Timor.

Towards the Referendum

Indonesian President Suharto resigned in 1998. In May, his successor, B.J. Habibie, offered autonomy for East Timor. Independence was not under consideration as Habibie though this would violate Indonesian sovereignty. His proposition suggested that Indonesia would retain authority on East Timor on issues of foreign affairs, defense, and monetary and fiscal policies. In a meeting in August 1998, the Portuguese and Indonesian foreign ministers with the U.N. Secretary General discussed the details on what the autonomy for the territory would look like. Indonesia insisted on its autonomy proposition as the final status for East Timor, while Portugal envisioned this only as a temporary or transitory situation that would lead to full independence.

Internal East Timorese actors were incorporated into the debate. Indonesia agreed with the U.N. in 1995 to hold annual talks with local actors on several policy issues, but under the condition that the status of East Timor was not discussed. Indonesian authorities argued this topic had been decided upon and settled by the Regional Popular Assembly in 1976. Yet, by the late 1990’s Indonesia came to terms with the idea that the East Timorese were not satisfied with the Suharto or Habibie administrations. In April 1998, local political actors united under the National Council of Timorese Resistance, led by Gusmao, still imprisoned. While pro-independence activism became more open, pro-integration militias staged several raids against those who opposed Indonesian authority in East Timor.

Violence increased in East Timor. Largely for this, neighboring Australia estimated that regional stability could be better served with East Timor being part of Indonesia, even if it was as an autonomous province. However, in a letter to President Habibie dated in December 1998, Australian Prime Minister John Howard suggested that the issue could only be settled with an open and direct participation of local East Timorese actors. In this sense, Howard ensured that the option of full sovereignty could not be ignored. In January 1999 this position was reconsidered by Indonesian authorities. Habibie’s government announced that if after consultations the East Timorese rejected the autonomy option (on whose details his ministers were still working), the Regional Popular Assembly’s 1976 decision to join Indonesia should be rejected.

Through the rest of 1998 and early 1999, tripartite consultations between Indonesia, Portugal and East Timorese leaders continued on the details of the autonomy plan, which was still the option favored by Indonesia, and on the means to decide which option would be picked. On May 5, 1999, an agreement was made public. A final autonomy plan was accepted by all parts, which would be put to a popular referendum by August that year. The Popular Consultation in East Timor Information Center documents the preparation of this ballot.

Bibliography

Ian Martin, Self-Determination in East Timor. The United Nations, the Ballot, and International Intervention, Boulder and London, Lynne Rienner, 2001.

Tim Fischer, Ballots and Bullets. Seven Days in East Timor, St. Leonards, Allen & Unwin, 2000.

Filomena Suares, “Bearing Witness”, Geoffrey Robinson, “If You Leave Us We Will Die”, and Erin Trowbridge, “Back Road Reckoning”, all in a special issue of the journal Dissent, vol. 49, Winter 2002.